Stability Over Symbolism: Debunking Bekolo’s Case Against President Paul Biya

In Defense of Continuity: A Rebuttal to Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s article: “Paul Biya contre l’Histoire: Quand un homme efface un siècle de dignité Africaine” (Paul Biya Against History: When a Man Erases a Century of African Dignity).

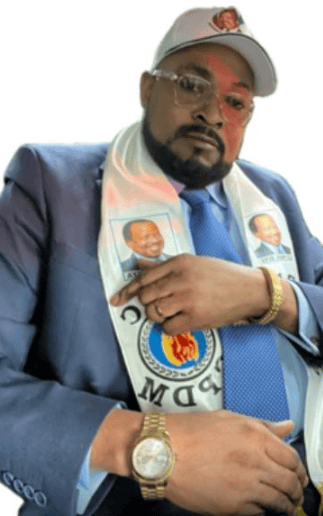

Dr. Julius B Taka

7/20/2025

Abstract

This article is a reply to Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s polemical essay, which argues that H.E. Paul Biya is denying Africa its intellectual and moral inheritance by clinging to power. I suggest that Bekolo — an internationally acclaimed film director known for his bold, satirical, and genre-defying films — confuses symbols with substance, misreads Cameroon’s socio-political crossroads, and mistakes tactical politics for stagnation.

By way of African political history, leadership theory, and Robert Greene’s The 48 Laws of Power, I argue that Biya’s cautious and adaptive leadership has preserved Cameroon’s sovereignty, stability, and dignity in ways that demand closer, more nuanced scrutiny.

Introduction

Bekolo depicts President Paul Biya as the living replica of colonial stereotypes: useless, blind, and a negator of Africa’s dignity. Despite its rhetorical force, his analysis fails by oversimplifying Biya’s rule and the historical circumstances shaping Cameroon today.

In postcolonial Africa, leadership calls for a strategic blend of change and continuity, grand vision and discipline — concepts Greene (1998) identifies in his 48 Laws of Power.

This article responds to Bekolo in five points: Biya’s longevity and historical dignity, intellectual endowment and pragmatic action, the caricature of stagnation versus stability, the defense of African dignity and sovereignty, and finally, Biya as strategist rather than saboteur.

Longevity and Historical Dignity

Bekolo claims Biya’s longevity erases “a century of African dignity.” African history, however, suggests the opposite. Leaders who maintain unity, prevent bloodshed, and resist external domination often strengthen, not weaken, national dignity (Mbembe, 2001).

As Greene (1998) advises: Law 1: Never outshine the master; Law 45: Preach the need for change but never reform too much at once.

Biya’s durability stems from a keen awareness of Cameroon’s fragile ethno-political balance. Despite destabilizing shocks that fractured states like Libya, the Central African Republic, and the DRC, his governance has preserved Cameroon’s sovereignty and stability (Biya, 1987).

Intellectual Legacy: Rhetoric Versus Pragmatism

Bekolo laments that Biya betrays Africa’s intellectual giants — Diop, Fanon, Nkrumah, Sankara — by refusing revolutionary fervor. Yet governance is not judged by rhetoric but by adapting ideals to reality.

Even Fanon (1963) warned that undisciplined revolutions lead to chaos. Greene (1998) similarly notes: Law 3: Conceal your intentions; Law 36: Disdain that which you cannot have.

Biya has practiced quiet diplomacy and incremental development, avoiding the revolutionary excesses that doomed other regimes. Silence, in his case, is not betrayal — it is survival.

Caricature of Sloth Versus Benevolent Stability

Bekolo portrays Biya as the embodiment of colonial stereotypes: laziness, corruption, tribalism, fixation on power. This caricature ignores Biya’s skillful use of patronage networks, moderate reforms, creative ambiguity, and measured adjustments to keep Cameroon intact (Mbembe, 2001).

What some call immobility is better described as managed stability. Power vacuums often lead to civil war or foreign intervention — both absent in Cameroon. Greene’s wisdom applies: Law 23: Concentrate on your forces; Law 48: Assume formlessness.

Biya has retained power where it matters — national unity — while eluding both internal opponents and external manipulators.

African Dignity and Sovereignty

Bekolo equates dignity with departure, citing Mandela’s example. Yet Mandela left behind structural inequities. Dignity also lies in protecting independence, resisting neocolonial interference, and guiding nations through fragility (Nkrumah, 1963).

Biya has shielded Cameroon from the chaos that engulfed its neighbors, thereby affirming Africa’s sovereignty — a silent, austere assertion of dignity.

Paul Biya as Strategist, Not Saboteur

Bekolo mistakes Biya’s strategy for stasis and his silence for complicity. In reality, Biya’s rule represents mastery of subtle political arts.

Greene (1998) reminds us: Law 4: Always say less than necessary; Law 15: Crush your enemy totally; Law 45: Preach change, but never all at once.

Biya’s persistence reflects not weakness but skill — a deft ability to navigate the perilous terrain of postcolonial Africa. Far from erasing dignity, his leadership has preserved Cameroon’s unity and sovereignty amid turbulent times.

Bekolo’s concerns about reform are valid and deserve debate. But his framing of Biya as anti-African misrepresents the complex realities of post-independence politics.

References

Bekolo, J.-P. (n.d.). When Man Shuts History: Paul Biya and a century of African dignity. Unpublished essay.

Biya, P. (1987). Communal liberalism. Paris, France: Éditions Pierre-Marcel Favre.

Fanon, F. (1963). The Wretched of the Earth. New York, NY: Grove Press.

Greene, R. (1998). The 48 Laws of Power. New York, NY: Viking.

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the Postcolony. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1963). Africa Must Unite. London: Heinemann.